A Candid Look at the Brain on Drugs

Recent advances have shed light on how the brain responds to various addictive substances, ranging from depressants like heroin, morphine, barbiturates, tranquilizers, and alcohol, which slow down brain and central nervous system functions, to stimulants like cocaine, amphetamines, nicotine, and marijuana, which generally have an excitatory effect.

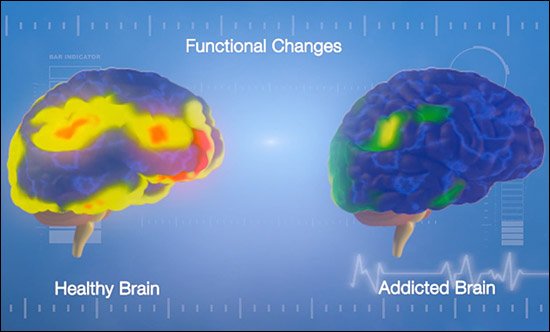

As the central organ affected by addiction, the brain’s cells, or neurons, respond to external stimuli, including drugs, as well as to internally produced hormones and chemicals. These interactions trigger a cascade of chemical reactions that influence movement, thought, emotions, and memory. Drugs of abuse either enhance or disrupt the brain’s chemical messengers, known as neurotransmitters. These neurotransmitters are crucial for addiction and are released by the brain’s approximately 10 billion neurons involved in transmitting information.

Neurotransmitters circulate within the brain and bind to specific receptor proteins on the surfaces of adjacent cells. Each receptor is uniquely shaped to “recognize” and bind to a specific neurotransmitter, similar to how a lock fits a particular key. Once a neurotransmitter binds to its receptor, it can transmit its signal to the next neuron. If a neuron is exposed to excessive amounts of a neurotransmitter, a sophisticated “control” mechanism called “reuptake” is normally triggered. This process allows the neuron to reabsorb the excess neurotransmitter for future use, preventing an overabundance of chemical signals that could lead to excessive neural activity and potentially severe mental and physical issues.

However, neuroscientists have discovered that certain substances of abuse can interfere with this delicate balance. Some drugs block the reuptake process, resulting in an excess of neurotransmitters, while others inhibit neurotransmitter release. Although many neurotransmitters and neurotransmitter-like chemicals have been identified, those most closely associated with addiction include norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, substance P, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

In 1973, Solomon Snyder, M.D., a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins University, and his graduate student Candace Pert made a groundbreaking discovery that helped establish the modern understanding of addiction. They identified opiate receptors in the brain by tracing radioactive-labeled drug molecules to their binding sites. Their research demonstrated that drugs like heroin and morphine bind to these receptors, while methadone, a weaker synthetic opiate, binds less tightly. Methadone satisfies an addict’s cravings because it binds to opiate receptors, but it does not produce a “high.”

Snyder and Pert realized that their discovery had profound implications. If the brain had specific receptors for opiates, it wasn’t because humans were naturally inclined to heroin addiction; rather, it suggested that the body must produce its own opiates. This led to the discovery, in 1975, of naturally occurring opiates in the brain, known as endorphins and enkephalins. These findings provided evidence of neurochemical sites of pleasure within the brain, which are naturally activated by human activity.

Subsequent research revealed that exogenous opiates (such as heroin) keep opiate receptors persistently occupied, resulting in physical tolerance, a hallmark of heroin addiction. The brain of an opiate-addicted individual also appears to downregulate or reduce the number of active receptors, leading to desensitization and the need for increasing doses to achieve the same effect.

Scientists also discovered that cocaine primarily affects nerve cells in the brain’s limbic system, an ancient area closely associated with emotions. Rather than binding to a specific receptor, cocaine interferes with the reuptake process that normally ends the action of dopamine. Cocaine also blocks the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, resulting in an overstimulation of nerve cells. This overstimulation leads to intense feelings of euphoria and excitement. However, after the initial high, cocaine depletes the brain’s available supply of these neurotransmitters, leading to withdrawal symptoms characterized by severe depression, paranoia, irritability, and intense cravings.

According to Steven Childers, psychedelic drugs such as LSD and psilocybin (“magic mushrooms”) differ from other substances of abuse in that they do not primarily activate the brain’s ancient reward system regulated by dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. Instead, these drugs affect areas of the brain involved in higher cognitive functions rather than emotions and pleasure. As Childers notes, these substances are often pursued not for addictive purposes but to alter mood and enhance consciousness. This distinction helps explain why their effects on the brain are different.

Tranquilizers, such as barbiturates and benzodiazepines (e.g., Valium), also affect the brain differently. These drugs do not have their own unique receptors but instead act on “foster” receptors, specifically GABA receptors. GABA is a neurotransmitter primarily responsible for inhibiting neural activity. Tranquilizers enhance GABA’s inhibitory effect, leading to sedation. As Childers explains, these drugs “hyperactivate inhibition,” which essentially means they increase the brain’s inhibitory signals, leading to sedation or, in extreme cases, shutting down brain activity altogether. Alcohol also acts on GABA receptors, while amphetamines disrupt dopamine balance and nicotine, in high doses, triggers the release of endorphins.

Understanding the diverse ways in which different drugs interact with the brain’s complex neurochemical systems highlights the challenges involved in treating addiction and the importance of tailored approaches for effective intervention and recovery.